From Fox News Latino, November 23, 2012

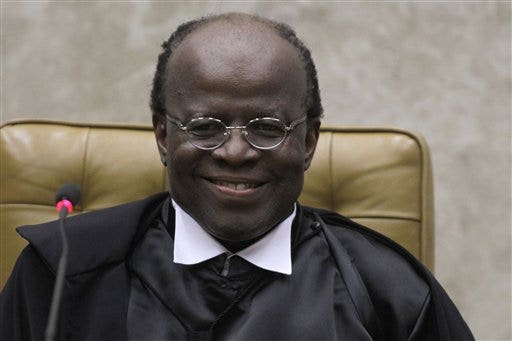

BRASILIA – Joaquim Barbosa was sworn him on Thursday, making him the first black justice to head Brazil’s Supreme Court.

The 58-year-old became the first ever to serve on the court when he joined in 2003, even though more than half of the country’s 192 million people identify themselves as having African descent.

Barbosa was elected in October to a two-year tenure as Supreme Court President. His election was a foregone conclusion since the court’s presidency always goes to the justice who has served on the bench the longest.

Over the past several weeks he gained national and international renown presiding over a high-profile corruption trial involving a congressional cash-for-votes scheme. The court has convicted 25 people including the fort chief of staff of ex-President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

President Dilma Rousseff, members of her Cabinet, state governors, congressional leaders and several sports and entertainment personalities were present at Barbosa’s swearing in.

“The multiculturalism that characterizes the Brazilian people is evident here today with Joaquim Barbosa heading the highest court of the land,” said Ophir Cavalcante, president of the Brazilian Bar Association in a speech during the swearing in ceremony.

Valter Silveiro, coordinator of the Center for Afro-Brazilian Studies of the University of Sao Carlos, believes Barbosa as a Supreme Court president “has a strong symbolic impact for Brazilian blacks.”

“The new generation of blacks will have the opportunity that my generation never had — of seeing a black man presiding over one of the three branches of government.”

Silveiro also stated Barbosa's history, background and achievements "strengthen affirmative action programs that try to increase the presence of blacks in the country's universities."

Barbosa was born in the small town of Paracatu in Minas Gerais state, where his father worked as a bricklayer. When he was 16 he went to the capital, Brasilia, to study. He worked as a cleaner and a typesetter at the Senate to pay for his studies at the University of Brasilia’s law school.

After graduating he was hired by the Foreign Ministry and served three years at the Brazilian Embassy in Finland.

A former federal prosecutor, Barbosa taught law at Rio de Janeiro State University and was a visiting scholar at the Human Rights Institute of Columbia University’s law school in New York and the UCLA law school in California.

Based on reporting by the Associated Press.

http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/politics/2012/11/23/brazil-selects-first-black-supreme-court-president-joaquim-barbosa/